Reading Extended Response Text Proof, Elaborate, Closing Thoughts

Supporting students to get their knowledge prepare for learning is an of import stage in reading comprehension and links closely to the Victorian Curriculum (VCELY412, VCELY443).

Activating prior knowledge (speaking and listening, writing)

Munro's (2002) high reliability literacy teaching strategies shed light on the differences between students' existing knowledge and the new knowledge they are expected to internalise when reading. This departure between existing and new cognition is the source of many difficulties students face when reading.

Two activities that enable students to activate their prior knowledge earlier reading include:

- Thinking with prompts

- Using word clouds/brainstorms.

The examples below support reading Jasper Jones (Silvey, 2009) in a Year 9 or 10 class.

- Open all

- Close all

Thinking with prompts

Students are provided with visual, written or verbal prompts nigh an upcoming text.

These prompts might be a drove of images or visual representations of the larger themes in the text. In the example of Jasper Jones, the following visual prompt is an paradigm that speaks to the theme of 'scapegoating'.

Questions are used to encourage students to make connections between their existing knowledge and the knowledge that will exist explored in the text.

Questions that could exist used include:

- Have y'all heard of the novel or film, Jasper Jones?

- Accept you heard of To Kill a Mockingbird?

- Accept y'all heard the phrase 'coming of age' before? What do you think it means?

- What other Australian films take you seen? Which ones stand out to yous

- Looking at the cover, what inferences can you lot brand about the characters, plot and themes? Students may observe that both characters expect worried, that a romance is a sub-plot, that the story takes place in a small town, and they may hash out the colours in the cover, including skin tones and the colour of the heaven above each boy'south head.

While the teacher can lead the grade in a give-and-take of these questions, students' responses could be collated in a digital collaborative space and so referred to every bit the text study progresses.

Word clouds and brainstorms

Word clouds and brainstorms are an easy only constructive way for teachers to quickly institute what learners may know about a particular topic.

There are many online resources bachelor that let students to interactively create word clouds (run into example below), or to collaboratively respond, record and revise question prompts earlier, during and subsequently reading.

To initiate a word cloud:

- The instructor states a fundamental word (or uses the cover of the novel every bit a prompt).

- The teacher asks students to tape all of the words that come to mind when they call up almost that term.

- The teacher moderates student sharing equally synonyms and examples are shared by students and added to the word cloud.

- The teacher takes note of educatee prior knowledge and can target time to come student learning (e.g. about historical context or genre conventions).

The activity can be altered and so that students are organised into groups with each grouping focusing on a different attribute of the text that is to be read. Alternatively, groups of students could write responses on butcher's paper or digital whiteboards and and so rotate around the room, reviewing and adding to the notes written by the other groups.

Prototype created with world wide web.wordart.com

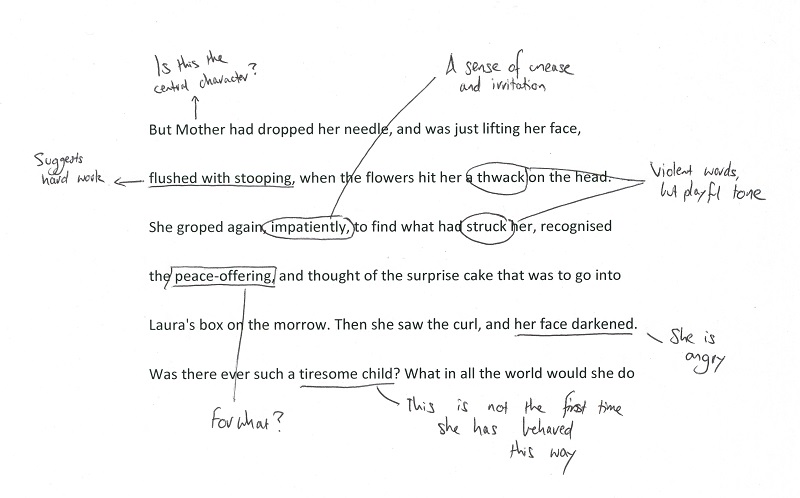

Annotating text (reading and viewing, writing)

English language teachers oftentimes employ annotations as a way to back up students with their comprehension and to develop a closer reading of texts.

1 way to exercise this is to guide them to identify the key words, quotes, sections or passages within the text, and makes notes as they go. The annotations form ii functions, to help with agreement and to be a reference point for revision at a afterwards stage of learning.

When students learn to annotate text, for instance, by underlining central words or writing the main idea in the margin, which students tin be guided to exercise on both electronic and paper texts, they should exist provided the opportunity to talk to each other well-nigh the text using their annotations. This volition help them to:

- further develop their interpretations

- challenge others' interpretations

- explain the processes by which they came to their interpretations

- learn how others read and translate texts.

Putting into words both interpretations and thought processes adds to students' awareness of the strategies they are using and the characteristics of texts.

A teaching model of how to annotate a text is an important step in edifice students' independence with their ain reading and note-taking.

A set of step-by-step instructions about how to approach annotations is too crucial.

Annotations:

- Ask a question.

- Look for the answer to the question.

- Circle a discussion you don't sympathize (look upwardly its meaning).

- Underline an important quote (line or phrase).

- Make a connection (how does this relate to something else you've seen or read?).

- Requite an stance.

- Look for clues to assistance draw an inference.

- Retell what has been read (brand summary note).

- Visualise a moving picture.

Curriculum links for the higher up example: VCELT461, VCELT465, VCELY466, VCELY467.

Literacy in Practice Video: English - Think-Alouds and Annotating Texts

The following video demonstrates how to use modelled reading with retrieve-alouds and how to model annotations in a Year 7 English class.

This was a double lesson of English with team didactics. After reading the text and modelling text annotations, the learning focussed on the difference between formal and informal language. The teachers apply text letters as an example of informal communication.

Teaching notes offer more details virtually this English lesson that included the learning intentions, rationale, Victorian Curriculum links, the literate demands and assessment, and the learning and teaching stages in this video segment.

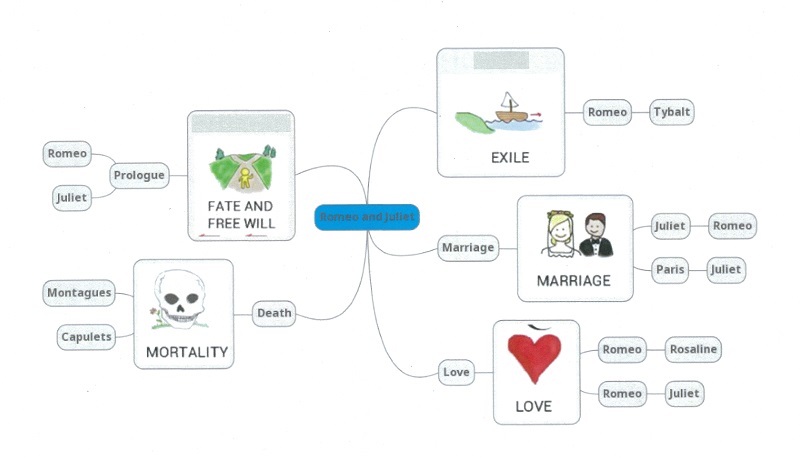

Concept mapping (reading and viewing, writing)

In concept mapping, students acquire to place important relationships that capture text structure and to represent these in a diagram (Armbruster & Anderson, 1980).

Mapping requires students to engage with meanings in text, to search for detail textual and linguistic features, and to transform these features into a diagram representation. The result is a educatee-produced diagram that uses symbols to capture interconnected textual features.

Armbruster and Anderson (1980) describe mapping every bit a technique which tin can be varied to suit the reader's purpose. Students acquire to search for key words or other linguistic or textual features and to brand connections betwixt these. Students are and then introduced to symbols, which are used to map relationships betwixt different features of the text.

Fisher, Frey and Hattie (2016) suggest that concept mapping is most effective when it is used as a tool for students to show their thinking and to organise what they know. In other words, a concept map should not be considered an end-product; rather, it is an intermediate stride that students tin employ to complete another task (Fisher, Frey & Hattie 2016, p. 80).

The post-obit concept map was produced by a Year 10 educatee to unpack the relationships between themes and characters in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet (VCELY467, VCELY468, VCELY469).

Teachers can provide further scaffolded instructions to support students to elaborate on themes and identify key textual events and quotes to support subsequently essay writing. Case instructions below.

For each:

- connecting line: write a word or sentence to describe the relationship

- character: identify an action or quote that demonstrates how they relate to the identified theme

- theme: listing the imagery or symbolism that Shakespeare uses. For example, sun for Juliet.

Close reading (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Shut reading is a method of engaging with literary texts. Snow and Connor (2016) ascertain shut reading as "an approach to instruction comprehension that insists students extract significant from text by examining carefully how language is used in the passage itself" (p. ane).

Shut reading supports students to explore the means that ideas and viewpoints in literary texts come from different historical, social and cultural contexts. It also supports students to think near how these contexts may reflect or claiming the values of individuals and groups.

The main intention of close reading is to appoint students in the reading of circuitous texts. Fisher, Frey and Hattie (2016, p. 89) outline four elements to support close reading:

- repeated reading of a curt text or extract

- note of the brusk text or excerpt to reflect thinking

- teacher's questioning to guide analysis and word

- students' extended discussion and analysis.

Wheeler's (n.d.) half-dozen-approach to shut reading

Wheeler (n.d.) offers a six-stage approach to close reading.

This approach is modelled using Shaun Tan's 'The Water Buffalo' from Tales from Outer Suburbia (2008), to show how repeated readings can exist used to support Year 8 or ix students to read the text in a structured, specific and sustained manner (VCELT403, VCELT438, VCELT439).

First impressions

- What is the first affair yous notice about the passage/s? What is the second thing?

- Students might find the briefness of the story, and that they take many questions that are unanswered past the text.

- Do the things you noticed complement or contradict each other?

- Students might notice that the short length of the text causes details to exist missing, such every bit what kind of communication the children asked of the Water Buffalo.

Vocabulary and diction

- Which words practice y'all discover offset? Why? What is interesting near this word selection?

- Students may notice the word 'consult' standing out in stark contrast to the more everyday language of the previous paragraph.

It sounds more formal and adult than the flick created in the previous paragraph, ie "water buffaloes are similar that; they hate talking". This contrast between the utilize of everyday and formal language could be the impetus for a discussion most authorial choice and affect of language.

Discerning patterns

- Does an paradigm hither remind you of an image elsewhere in the book? Where? What's the connection?

- Students may observe the similarities to the abruptness of 'Tales from Outer Suburbia' short story 'Eric', where a character is suddenly gone, and a similar sense of mystery surrounds them.

Betoken of view and characterisation

- How does the passage(s) make us react or remember about whatever characters or events within the narrative?

- The teacher could frame this discussion as a list of questions for the buffalo, in response to the mystery caused by the omitted details.

Symbolism

- Are in that location metaphors? What kinds? How might objects represent something else?

- The teacher could pose this question as: Who do children frequently become to for advice? Who might the buffalo represent in their lives?

Lenses

- How tin the meaning of words and sentences change when we await through a particular lens?

- Possible lenses could be: which words sound like they vest to a fantasy text, and which ones might sound more similar a factual recount?

The six-stages don't demand to be in order. Furthermore, yous may wish to include other activities to complement the six-stage approach.

What is important is that students are supported with multiple readings, each of which adds to the previous, with the stop goal of a more complex understanding of the text.

Literacy in Practice Video: English language - Comparative Assay

The instructor in this video is engaging Level x English students in a comparative assay of 3 texts in a close reading task. This video was recorded in a double lesson in preparation for a comparative essay chore. The lesson begins with students reading independently, and so moving into small groups to compare the texts and find bear witness showing how individuals in these texts were trapped by social norms.

Pedagogy notes offering more details about this English lesson that included the learning intentions, rationale, Victorian Curriculum links, the literate demands and assessment, and the learning and teaching stages in this video segment. Sample text used in video for comparative analysis in a pocket-sized group activity.

Decoding visual images (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Teaching students the metalanguage to speak and write about visual images is key for them to be able to read, interpret and analyse visual texts.

According to Kress and Van Leeuwen (1996), visual images are read as 'texts' and contain a 'grammar', that is, a set of socially synthetic resources to brand meaning.

Metalanguage for visual analysis

For example, an advertizement billboard containing a static visual image with foreground and background, accompanied by printed language, in the form of a tagline and company name, contains a structure which guides how the advert is designed to be read past an audition.

In the digital globe where students are increasingly exposed to a variety of multimodal and interactive texts, students crave the linguistic communication to be able to decode images too as to brand meaning from them.

Some of this language may be appropriated from the written report of literary texts, however, new terms will also need to be introduced into the classroom which recognise the unique communicative capabilities of these texts. See the table on Metalanguage for Visual Assay below.

| line shape size proportion | colour medium light shadow | perspective positioning framing cropping backgrounding foregrounding |

Guided questions to discuss images

An effective mode for teachers to introduce visual images to students is through the give-and-take of a still epitome. The teacher deconstructs the text with students, introducing and modeling the utilise of advisable metalanguage. The deconstructed image may come up from a form print text or may be a still from a film or moving image.

Analysis of an paradigm

Sample educatee responses to questions about the prototype.

- Where is your middle kickoff drawn to? My eyes go straight to the daughter in the middle of the epitome.

- Describe the key figure. The girl in the center of the epitome is a teenager who is reading a volume. She has long, blackness pilus. She is wearing a denim shirt and a pale pink summertime skirt. Her eyes are looking down at the book she is holding in both her hands. She has a smile on her confront.

- How is the central figure framed? The girl is framed by some bookshelves on both sides of the room she is about to enter. There is also a tree torso and its leaves at the archway of the room which is close to her right shoulder. Some of the branches form an arch over her caput.

- What are the details in the groundwork? There is a winding path behind the girl that leads to the room she is virtually to enter. The path runs through the middle of a forest.

- What are the details in the foreground?There is a brick flooring inside the room where the girl is standing. In that location are also some books scattered on the floor.

- How is colour used in the text? This paradigm contains soft colours inside the room that are mainly grey, merely with slight hints of other colours on the spines of the books. As my eye moves from the inside of the room to the outside, the colours become stronger and bolder. The colours of dark-green and brown stand out. The daughter's wearing apparel also contrast with the muted colours in the room.

- How are low-cal and shade used? There are two light bulbs positioned on the ceiling in the room. One light points downwards towards the daughter. This helps to make her the centre of the image. The other light faces i side of the bookshelf and it lights up the books so that the colours are slightly bolder.

- From whose perspective is the text presented? Information technology is every bit if a person is standing contrary the girl at the other end of the room looking inwards.

Using come across, think, wonder, similar to read a visual image

Students are provided with a photo, illustration or artwork to view. Teachers enquire students to record their initial reactions to the image through questions such as:

- I meet… (literal level of comprehension)

- I think… (inferential level of comprehension)

- I wonder… (inferential level of comprehension)

- I similar/dislike… (evaluative level of comprehension)

Initial student reactions

- I see a girl standing in the doorway of a room with books in it. There is a path and copse outside. Some of the copse are on the inside.

- I recollect the girl enjoys reading because she is looking down at the volume and she has a grinning on her confront.

- I wonder why the girl is there and what she is going to do when she goes into the room.

- I like the fashion the colours get stronger as y'all look out into nature. Information technology reminds me of a picture in a fairy tale.

These visual literacy strategies support curriculum objectives, in particular, VCELT407, VCELY411, VCELT418)

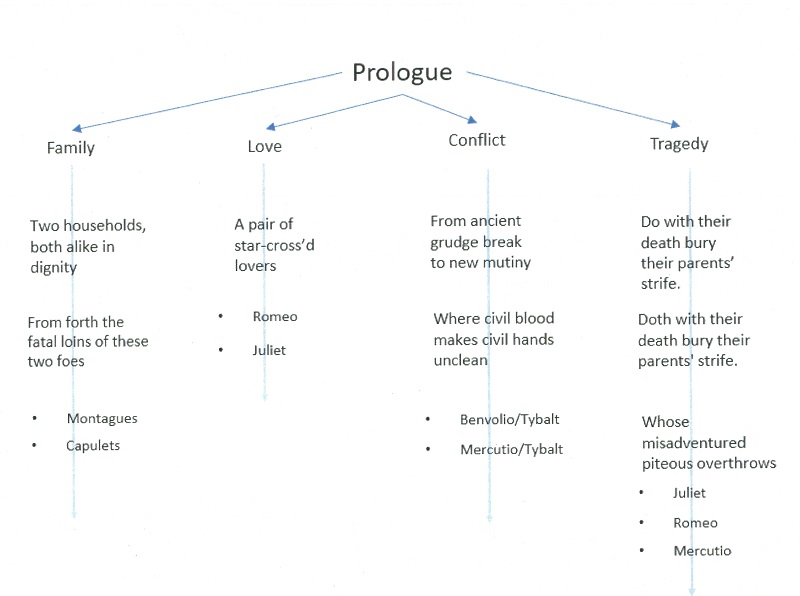

Flow-charting (reading and viewing, writing)

Period-charting is a tool for displaying the relationships between the features of a text. The menstruation-charting technique developed past Esther Geva (1984) requires a reader to utilize a nodes-relations organization to represent content and ideas. Nodes are points in a diagram or network that branch out to other nodes and demonstrate relationships.

Flow-charting can be used to demonstrate connections between the ideas or themes in texts, the literary features which assist realise these themes, and the structures that hold texts together. Depending on the focus of the flow-charting activity, it can be used to support pupil learning in relation to the following sub-strands of the Victorian Curriculum 7–ten: English:

- Text structure and organisation

- Responding to literature

- Examining literature

- Expressing and developing ideas

- Interpreting, analysing, evaluating.

Flow-nautical chart in do

For case, a teacher might use the following instructions to support students to produce flow-charts when analysing a literary text:

- Identify the key themes in this text, place them at the pinnacle of your folio.

- List three events from the text that the writer uses to explore each theme.

- Link private characters and quotes from the text that relate to each issue.

The following flow-nautical chart captures the ideas in the prologue to Shakespeare'southward Romeo and Juliet, every bit well as the textual knowledge that contributes to the germination of these ideas (VCELA473, VCELY467, VCELY469).

Guided questions (reading and viewing, writing)

Guided or guiding questions are questions provided to students, either in writing or spoken verbally, while they are working on a job. Asking guided questions allows students to motion to higher levels of thinking by providing more open-ended back up that calls students' attending to primal details without beingness prescriptive. This activity is role of Questioning (HITS Strategy vii).

Guided questions to back up teachers

Teachers tin use guided questions to back up students' comprehension of texts (VCELY378, VCELT438). This case provides questions that could be used when reading fiction and non-fiction texts. They tin can also be adapted for a set text.

This activity could be used for individual responses to a text or equally a group action lucky dip.

- The teacher presents each guided question on a split up piece of paper.

- The teacher asks students to select a random question from the gear up.

- The teacher asks students to reply to the question individually.

- The teacher asks students to share their responses.

- The teacher guides students through give-and-take near each question.

Worksheet example of Guided Questions

| Name any other stories that this story reminds you lot of. How did that connection help you to empathize the story better? | How are you lot alike or different from the primary graphic symbol in the story? |

| How did the story make you feel? When have you lot felt that fashion in your real life? | How does what you know virtually this type of text help yous better understand the story? |

| What other stories accept y'all read with similar characters or themes? How did that connection help you better understand the story? | What lessons did you learn in the story that can help you in your real life? Explain. |

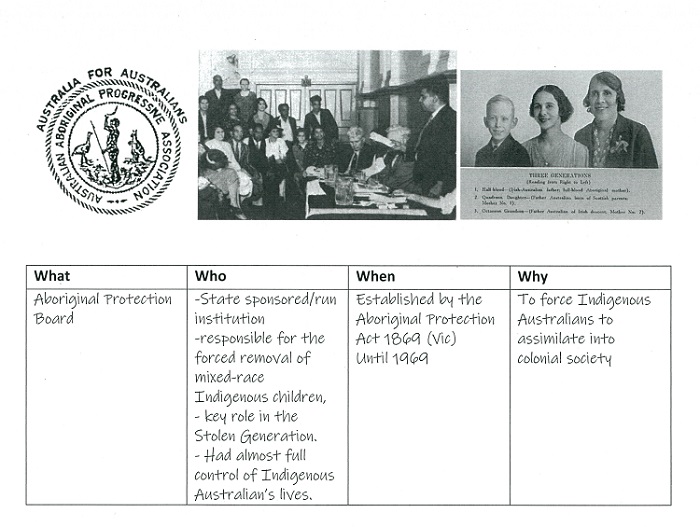

Initial field edifice (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Initial field building involves finding out what students know virtually a topic and so working with them to develop shared understandings which volition inform their choice of certain subject thing to include in their writing (Derewianka, n.d.).

In short, the purpose is to develop subject matter that will be the focus of student writing. The more students know about the topic, and the more language they use to express this knowledge, the better prepared they will be for writing with purpose and precision.

Edifice the field should be a social activity which include opportunities for conversations. While talk will often focus on information found in written and multimodal texts, information technology is important that the emphasis is on students' speech.

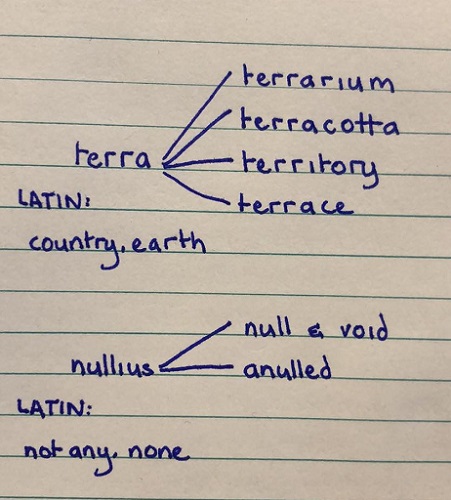

See building the field or context for a range of common tasks. The student work samples below demonstrate how ii of these tasks can be used to build the field for Year 10 students studying Claire G. Coleman'southward Terra Nullius (2017).

Research task about the Aboriginal Protection Board, a central attribute of understanding the text (VCELY466, VCELY469).

Edifice vocabulary through the study of Latin root words within the championship, 'Terra Nullius' (VCELA475)

Chiefly, building the field is not a 1-off phase or strategy. Rather, teachers should continue to support students to develop their understanding of a topic, including their vocabulary, equally they progress through various stages of writing.

Literal, inferential and evaluative questions (reading and viewing)

Reading comprehension is required across 3 levels

- literal

- inferential

- evaluative.

Literal comprehension occurs when the reader understands information that is explicitly stated within the text.

Inferential comprehension involves the power to process information so as to empathize the underlying meaning of the text (VCELY469). This is sometimes called 'reading between the lines'.

Evaluative comprehension occurs when readers gauge the content of a text by comparing it with:

- External criteria - where information technology agrees with what is by and large known or expected

- Personal criteria - how it fits with what individual readers know and what they value.

Teachers can use questioning which targets all levels of reading comprehension using literal, inferential, evaluative (50.I.E.) questions.

The following 50.I.E. questions could be used to support Year eight students' understanding of the below cartoon, and demonstrates how a teacher might motion a pupil from surface level to deep level understanding (VCELY411, VCELY412).

" src="https://www.education.vic.gov.au/PublishingImages/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/plot-hole.jpg">

Literal

- Who are the characters in this scene?

- What suggestion has the girl made to Miles?

Inferential

- Where is Miles?

- Why tin can't we see him?

- What is the boy on the right looking at?

Evaluative

- What does this drawing reveal about the writing process?

- What does the reader demand to know about stories to understand the comic?

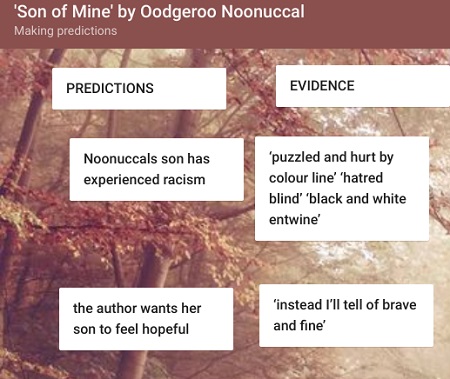

Predicting (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Skilful readers make predictions about what is coming upward based on available information, whether in the text or their ain experiences (both lived and textual).

These predictions change as the reader progresses through a text and new data becomes available.

Teachers can heighten reading comprehension past providing opportunities for students to make predictions prior to, and during reading (VCELY412, VCELY443).

The benefits of predictive activity are well-established (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983), and highlight the importance of drawing connections between: prior knowledge, predictions and reading content.

Predicting with classroom discussions

In Parkin & Harper'southward (2019) piece of work on teaching literacy through literature, classroom discussion is used to assist students to make predications as they read. Teachers support students in identifying clues in the text.

The teacher has students role-play the author equally they describe these 'clues' for prediction that the writer has left. The case beneath demonstrates how this activity could be used in a Year 7 class reading i of Paul Jennings curt stories, "Nails", from Unbearable (1990).

Teacher: Who would similar to be Paul Jennings today? Come on down Paul Jennings, and tell us about the foreshadowing in your story.

Student: Well, I've put in lots of foreshadowing in the story to requite you clues about how the story ends.

Teacher: So Paul, could you perchance explain to the audience what foreshadowing is exactly, because I think some of them aren't certain.

Student: Foreshadowing is little clues that I put in the story. Like when you're hiding and other people can only see the shadow. You know someone is there, simply you can't exactly see them.

Teacher: Ah yep, thanks. Does that help, audience? Keep going, Paul. What clues did you give?

Student: So I wanted the reader to know that the finish of the story was going to be about h2o. Then when Lehman looks at his female parent'south photo, she's got a gold clip with pearls in, because pearls come from the sea.

(Parkin & Harper, 2019, p.51)

This activity guides students in making informed predictions near the plot, only besides supports their agreement of the author'due south writing skill by identifying the author's purpose achieved (in this example, leaving clues to foreshadow a plot twist). This activity too models how to locate textual evidence and make inferences from clues.

Predicting with guided writing

Another manner for students to appoint in prediction is adapted from Hansen (1981). The teacher tin can ask students to:

- share what they know almost the circumstances probable to be faced by those characters in the narrative

- predict what the characters would do when confronted with unfamiliar situations in the stories that were notwithstanding to be read

- write down their prior knowledge answers and their predictions

- write a paragraph interweaving their prior noesis and predictions to strengthen their agreement that reading comprehension comes from what one knows and what is in the text.

Predicting with guided questions

Another way to engage in predicting work with students is to expose them to preparatory aspects of a text and to apply questioning to anticipate other parts of the text.

For case, students who are nigh to study a new novel might exist asked by their teacher to make predictions after the teacher has:

- Read the title and blurb aloud.

- Shown the grade a map that captures the master events.

- Provides a description of the main character.

- Read aloud the opening sentence or paragraph of 1.

Similar questions tin be asked for whatsoever text. For example, when introducing the poem 'Son of Mine' past Oodgeroo Noonucal to a Twelvemonth ix class, a teacher might activate student prior knowledge and prediction by asking the post-obit questions:

- What do you already know virtually Oodgeroo Noonuccal.

- What practise we know almost Commonwealth of australia'southward history that might help us guess what an Indigenous poet might tell her son?

- The kickoff line tells u.s. about the son's 'troubled eyes'. Tin can we predict what might be troubling her son?

Spider web-based brainstorming apps, such as Respond Garden and Padlet, can exist set upward to enable students to track their predictions, and the bear witness they collect both earlier and during reading.

Curriculum links for the higher up case: VCELA432, VCELT435, VCELT436, VCELT440.

Schematising (reading and viewing, writing)

A Schema is a cognitive or mental framework that we can construct in our heed to interpret or re-correspond aspects of our earth, including features of texts.

Visualisation can as well take place without the demand for the reader to produce any text. Students can be encouraged during both teacher read-aloud and silent or paired reading to interruption at specific points in the text to imagine what has been read. This could crave students to visualise a process, and and so verbalise or describe their mental epitome. Or, students could exist encouraged to use mental imagery to add visual characteristics to a scene or feature of a print text, improving their comprehension (VCELY411, VCELY443).

Subsequently reading aloud to Twelvemonth viii students the prologue to Glenda Millard'south A Small Free Kiss in the Nighttime (2009), the teacher might enquire students to close their optics and picture:

- Tia and the baby: What are they wearing? What are they doing?

- the carousel: How big is it? What state of repair is information technology in? What color is information technology? What practise the carts look similar?

- the fun park: What other rides are in that location? What might the ground look similar? Students are and so encouraged to draw and justify their visualisation of the text. The teacher tin can encourage students to apply evidence from the text and their own experiences to validate their interpretation of the text.

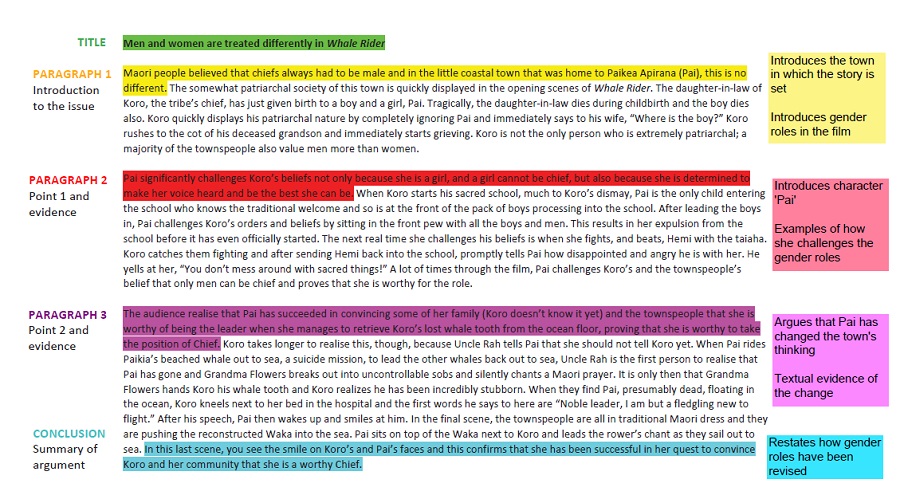

Using model texts to teach genre (reading and viewing, writing)

Before students are asked to produce a particular text, it is vital that they learn about the features of that genre (Derewianka, n.d.). This marks a shift abroad from the content of the writing, to the form, or craft, of writing.

Sometimes chosen 'modelling', explicit learning nearly genre provides students with cognition about the linguistic and structural features of the text. This tin can include explicit educational activity almost the stages of a comparative essay, persuasive text, or specific forms of text response.

Each genre unfolds in item stages and contains distinctive patterns. Learning about the genre allows students to identify the characteristic stages a genre contains in achieving its purpose (Derewianka, 1990).

For a range of strategies that teachers tin can perform with students when working with model texts for the purpose of learning the genre, see building the field or context. Below are two student samples that show how text marking and deconstruction can be employed in the English language classroom.

Literacy in Exercise Video: English language - Using Worked Examples

In this video, the teacher uses a model text 'The Simple Souvenir' to support a grade of year 8 students in developing the skills they need to write a comparative paragraph. This teacher offers constructive strategies to engage students in the process of deconstructing and co-constructing text that includes developing a metalanguage for students to talk meaningfully about the structure of the comparative text (eastward.yard., comparative words, text connectives and conjunctions).

Read the in-depth notes for this video.

Text marking

Annotating a text equally a class tin can exist a useful strategy to highlight unlike stages of the text, their purposes, and key features of the genre. 'Text marking' (Parkin & Harper, 2019) can be washed collaboratively using a concrete interactive whiteboard, or through interactive whiteboard spider web-based software through which all students tin collaborate.

Year ix model text response that has been marked upward during a teacher-led give-and-take (VCELY449, VCELY450, VCELY451). Image created using online software.

Group note tin can also be used to find or highlight fundamental words, phrases or sentences which assistance students' understanding of the text, and looking for patterns beyond texts.

Sequencing

Deconstructing and reconstructing the text can be useful to:

- explain how the parts of a text piece of work together

- explore sequencing and cohesive links, as well every bit markers of time.

As with text marker, teachers can jointly deconstruct a text with students and explicitly teach textual features. As students become more familiar with genre features, they can move towards independent deconstruction and reconstruction.

It tin can often take repeated encounters with model texts for learners to internalise their features. Students should be provided opportunities to come across and revisit genre features on multiple occasions so that understanding is reinforced (HITS Strategy 6: Multiple exposures).

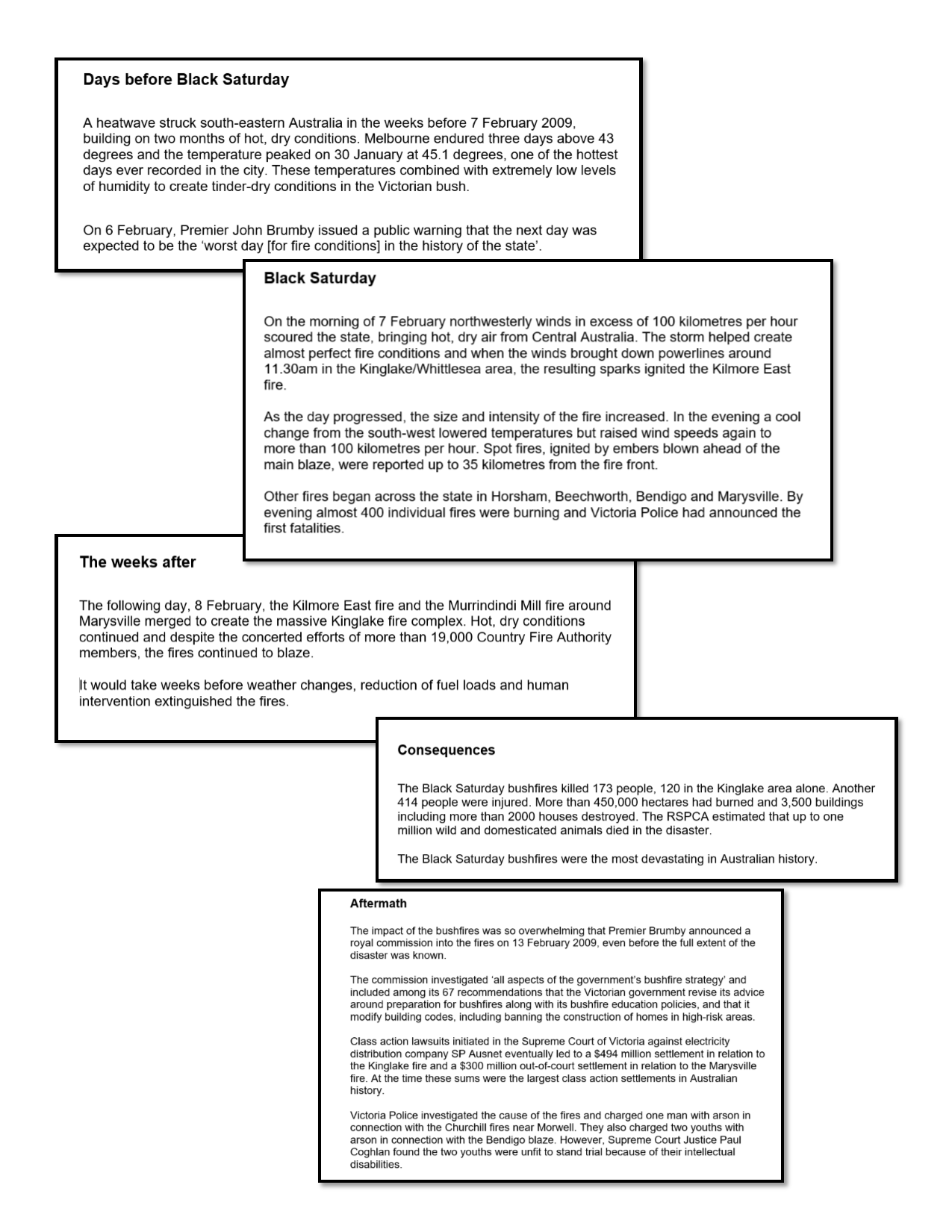

The post-obit worked example is from a Year 7 course and uses the online commodity, 'Black Saturday bushfires', published by the National Museum of Australia (VCELA380). Teachers could adapt this activeness to back up learning related to text construction and organisation at any level from vii to 10.

For this strategy:

- Students were given printed copies of the article, cut into sections.

- Students were asked to highlight key words that signal sequencing (such equally 'before', 'afterward' and 'aftermath')

- Students used these key words to arrange the sections in an gild that made sense.

- Students reviewed each other'due south reconstructions, justifying their choices and providing feedback to one some other. This offered opportunities to discuss more complex aspects of structure, such equally the ordering of 'consequences' and 'aftermath' that do not have a clear hierarchy to indicate where they should exist arranged.

View total size paradigm "Blended Graphics".

Additional tasks using model texts are:

- asking questions which require re-reading

- cloze activities creating flow charts or matrices to reflect connections between meaning and structure

- contrasting purpose and structure with a different genre

- For example, the information from the article on the NMA website (above) could be reworked into a brief fictional narrative, and the sequencing of events might be affected by the literary device of 'flashback' and 'flash forward' (VCELT385, VCELT386, VCELY387)

- finding other examples of the genre to compare

- For the case higher up, this could include other recounts of historical events that reflect on the aftermath, and integrate individual experiences into the text to varying degrees (VCELY378, VCELY379).

References

Armbruster, B. B., Anderson, T. H. (1980). The result of mapping on the complimentary retrieve of expository text (Tech. Rep. No. 160). Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Derewianka, B. (north.d). A teaching and learning cycle.

Derewianka, B. (1990). Exploring how texts work. Newtown: Primary English Educational activity Association.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for literacy, grades K-12: Implementing the practices that work best to advance student learning. Chiliad Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Geva, East. (1983). Facilitating reading comprehension through flowcharting. Reading Research Quarterly, eighteen(4), 384–405.

Hansen, J. (1981). The effects of inference grooming and do on young children's reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 16, 391–417.

Kress, G., & van Leuween, T. (1996) Reading images: The grammar of visual blueprint. London: Routledge.

Munro, J. (2002). High Reliability Literacy Teaching Procedures: A ways of fostering literacy learning across the curriculum. Idiom, 38(one), 23–31.

Parkin, B., & Harper, H. (2019). Teaching with intent 2: a literature-based literacy education and learning. Marrickville: Primary English Teaching Association Australia.

Snow, C., & O'connor, C. (2016). Close reading and far-reaching classroom give-and-take: Fostering a vital connectedness. Periodical of Education, 196(1), one-viii.

Wheeler, K. (n.d). Close reading of a literary passage.

innes-noaddeadied.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/Pages/paragraph_and_text_level.aspx

0 Response to "Reading Extended Response Text Proof, Elaborate, Closing Thoughts"

Post a Comment